MAY 25 - 30 2020

ONLINE ONLY

revisit the festival

CLOSING REMARKS

L’edizione 2020 del MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL si è svolta esclusivamente online per via della pandemia COVID-19. Da lunedì 25 a sabato 30 maggio, l’intero programma è stato presentato su questo sito.

Matteo Bittanti

The 2020 edition of the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL took place online, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. From Monday 25 till Saturday May 30, the entire program was available on this website.

Matteo Bittanti

Dal 2018, il MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL presenta al pubblico opere audiovisive sperimentali e d’avanguardia realizzate con i videogiochi - altrimenti note come machinima - da artisti e registi internazionali.

L’edizione 2020 del MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL propone opere di 25 artisti provenienti da 13 nazioni suddivise in 6 sezioni. La maggior parte di queste opere non sono mai state presentate in Italia.

Il programma completo è disponibile qui.

Un evento ufficiale della Milano Digital Week, il MACHINIMA FILM FESTIVAL è stato realizzato in collaborazione con GAMESCENES. Art in the age of video games e il Master of Arts in Game Design dell’Università IULM. Una prosecuzione della mostra GAME VIDEO/ART. A SURVEY (2016), porta a Milano produzioni idiosincratiche che si collocano all’intersezione tra video arte, cinema e videogiochi.

L’ingresso è gratuito e aperto al pubblico.

Seguiteci su Instagram & Twitter

IL TEMA DI QUEST’ANNO È

Since 2018, the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL has been showcasing avant garde and experimental game-based videos - also known as machinima - produced by filmmakers and artists from all over the world.

The 2020 MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL features the work of 25 artists from 13 countries, divided into 6 sections. The vast majority of these works have never been presented in Italy before.

The full program is available here.

An official event of Milano Digital Week, the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL is organized in collaboration with GAMESCENES. Art in the age of video games and the M.A. in Game Design at IULM University. A follow-up to the 2016 exhibition GAME VIDEO/ART. A SURVEY, it brings to Milan idiosyncratic video works that lie at the intersection of video art, cinema, and digital games.

The event is free and open to the public.

Follow us on Instagram & Twitter

THIS YEAR’S THEME IS

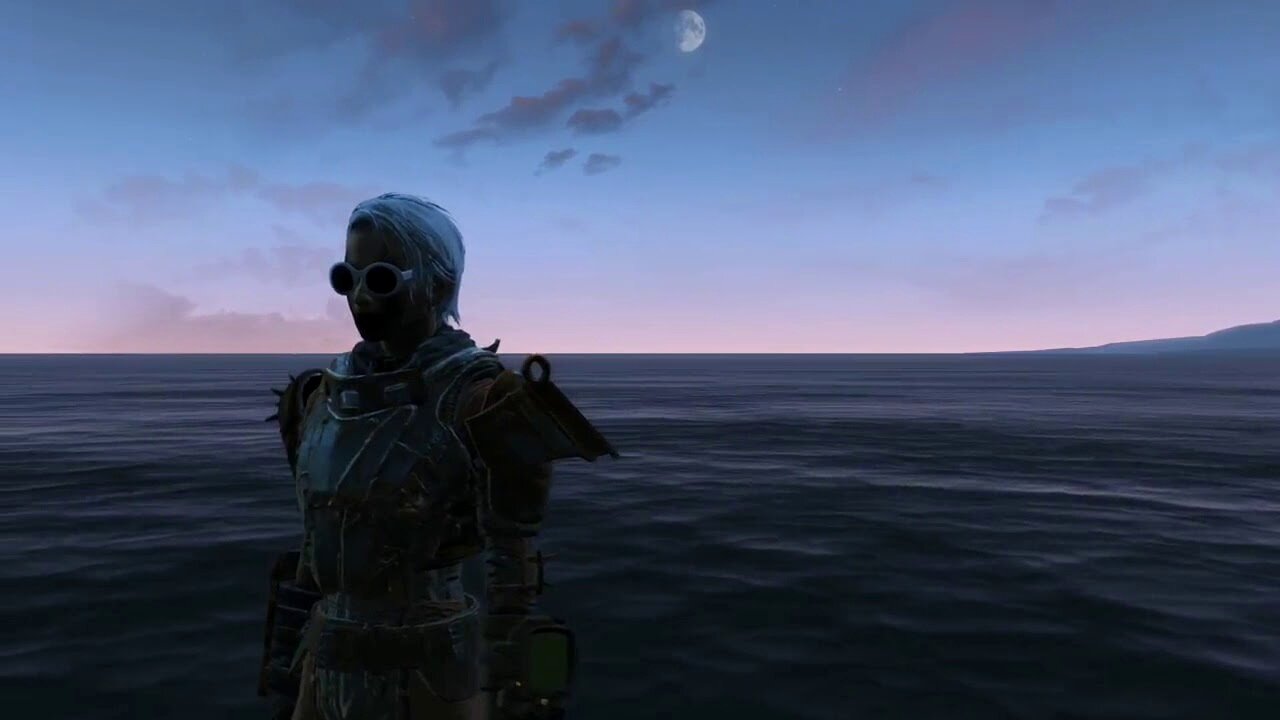

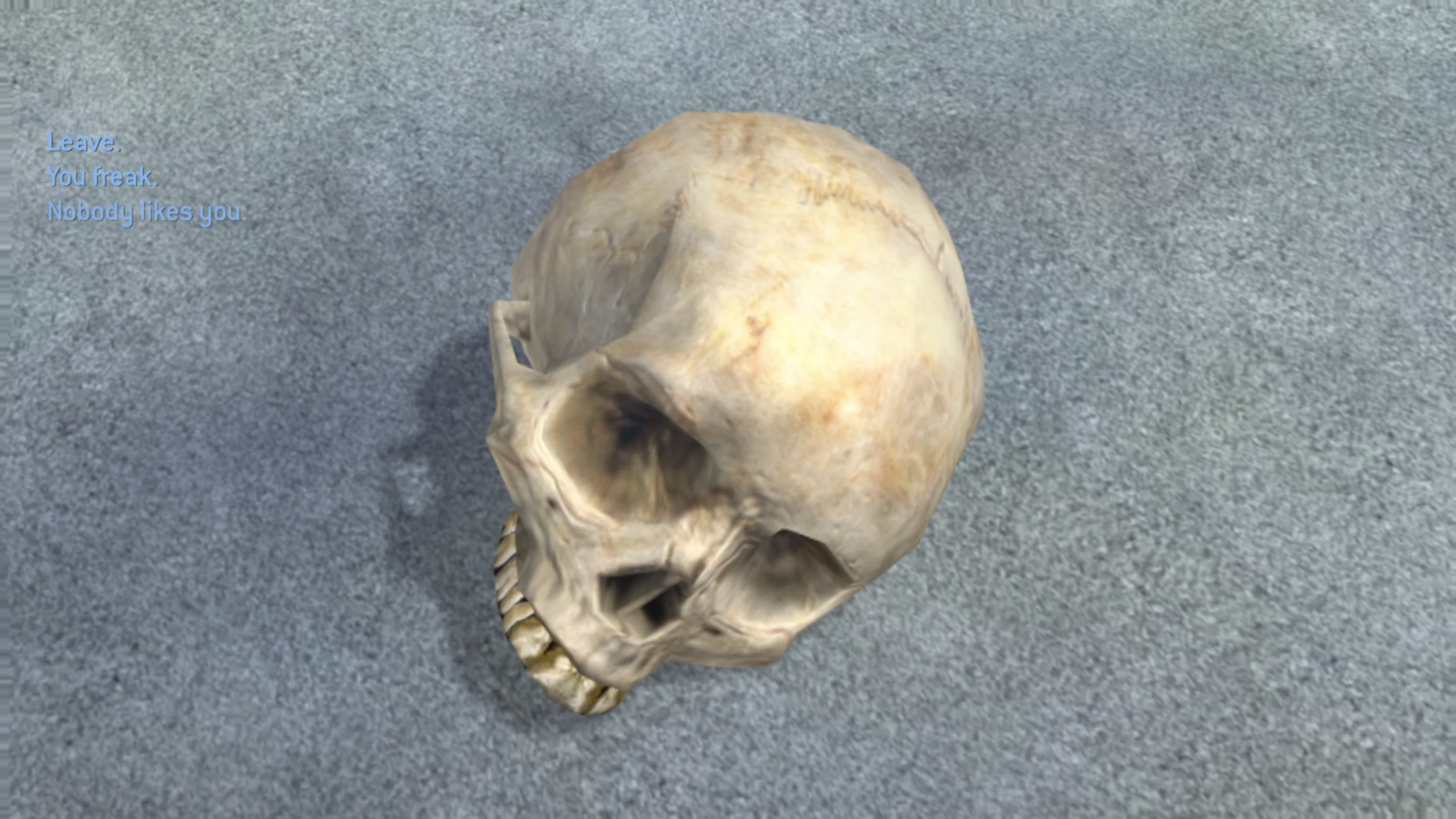

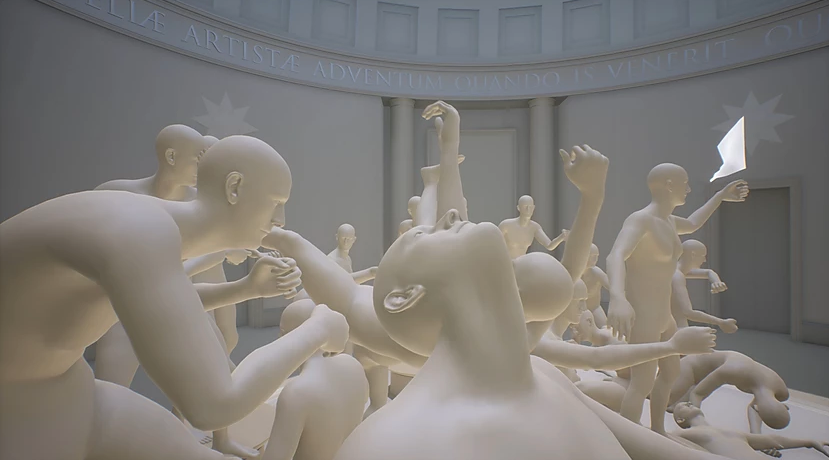

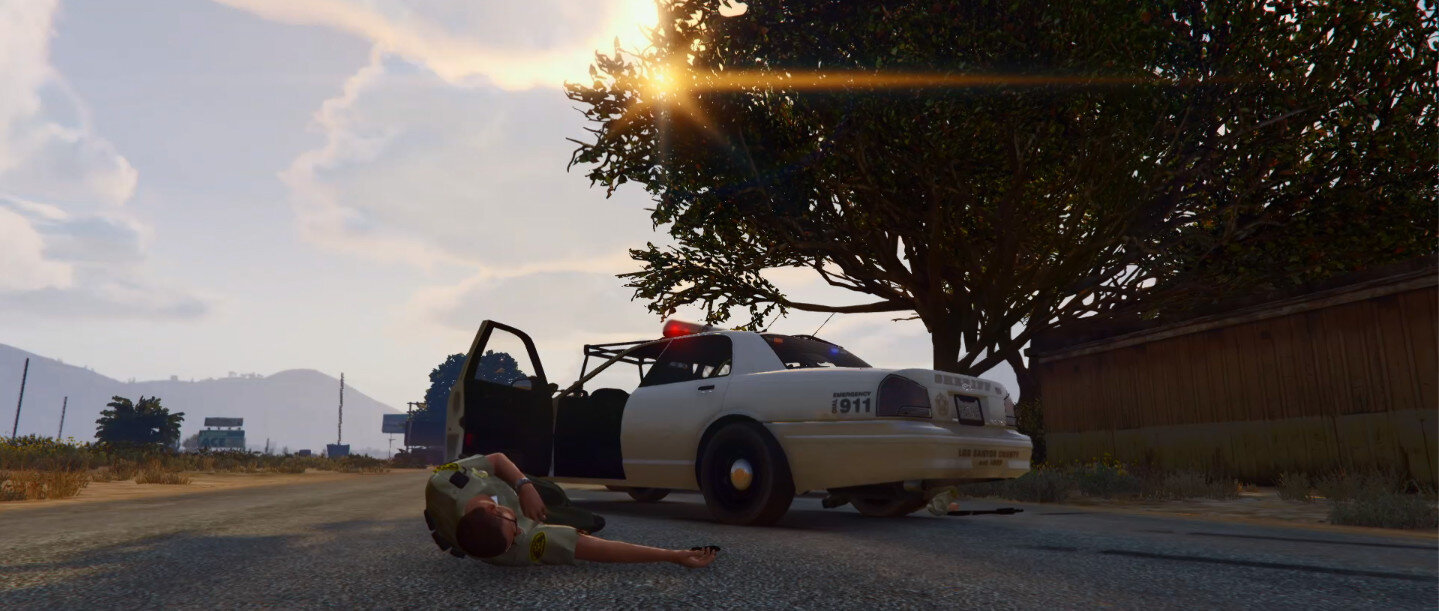

According to the late Mark Fisher (2017) “what the weird and the eerie have in common is a preoccupation with the strange”, which he defines as “a fascination for the outside […], that which lies beyond standard perception, cognition and experience.” Machinima is a strange medium indeed: it looks like videogame but behaves more like video. It aspires to the cinematic condition, but it is rarely projected onto a big screen. Fisher adds that “the weird and the eerie make the opposite move: they allow us to see the inside from the perspective of the outside”. Likewise, machinima allows us to see both the medium of cinema and video game from an outside perspective, as machinima is not cinema or videogame. Although it’s true that one can discern elements of both cinema and video game in machinima, machinima is something else altogether. This is weird.

There’s so much weirdness, i.e. “a particular kind of perturbation”, a symptom that something “does not belong” (Fisher), in machinima. Machinima is weird because, as a medium, defies categorization. Like cinema, machinima uses montage (“the conjoining of two or more things which do not belong together”) but unlike cinema, it is often indifferent to the real: it actively constructs new ways of looking at the world(s) and, by doing so, generates new realities. Machinima looks and feels wrong: unsurprisingly, Fisher talks about “a sense of wrongness associated with the weird”.This may explain machinima’s pendant for glitchy, distorted, uncanny situations. According to Fisher, wrongness, “the conviction that this does not belong is often a sign that we are in the presence of the new”. Indeed, machinima is still (relatively) novel: at twenty four, it is a young medium. Its weirdness “is a signal that the concepts and frameworks which we have previously employed are now obsolete”. Machinima is weird because “is notable for the way in which it opens up an egress between this world and others”. In other words, machinima is a bridge connecting different aesthetics, artworlds, and audiences. “It is the irruption into this world of something from outside”. Above all, the medium of machinima operates as a communication channel between the simulacra (non human or post-human entities) and living human beings.

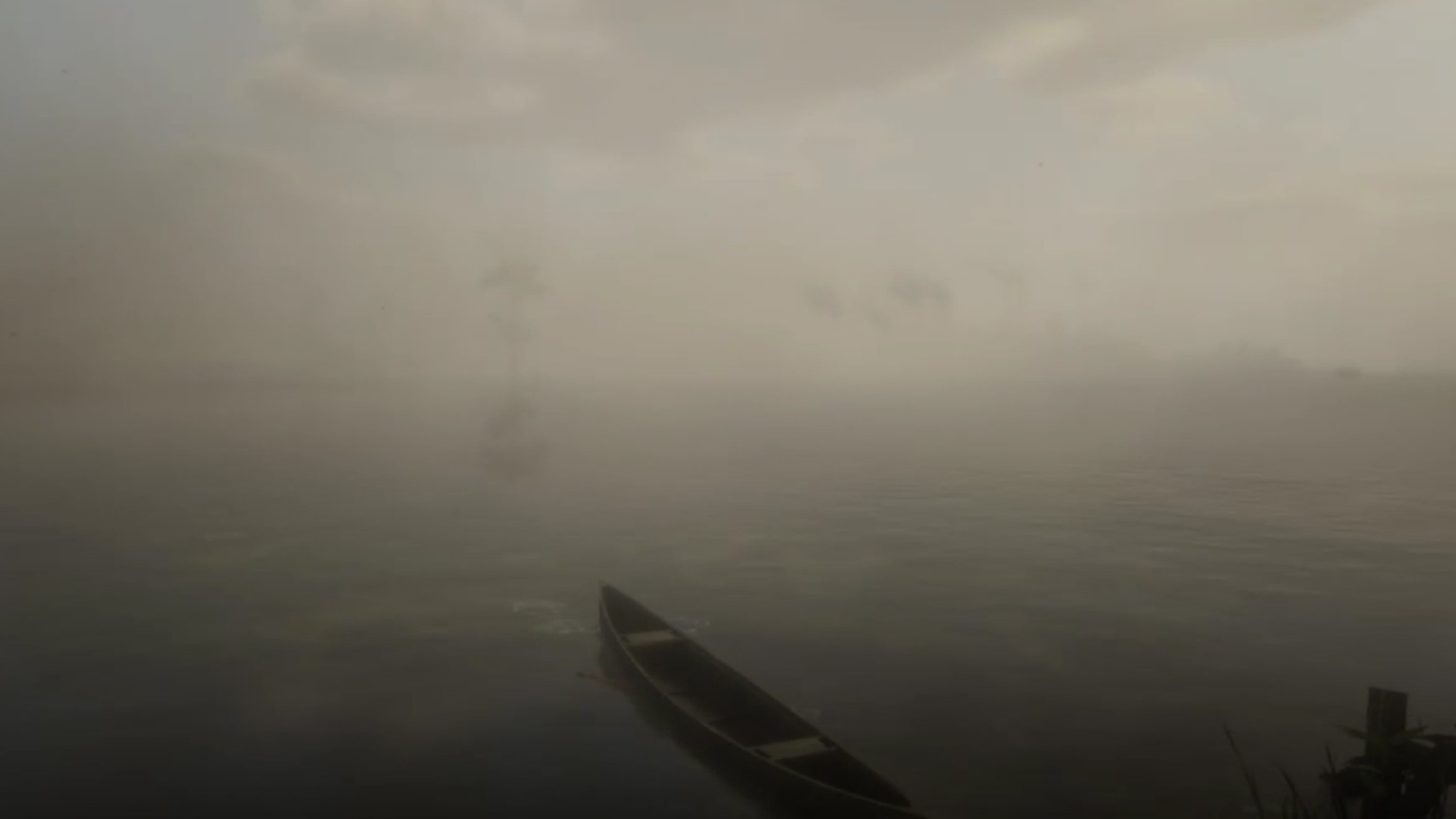

According to Fisher, the eerie can be found in “landscapes partially emptied of the human”. In a sense, all machinima are eerie because they are devoid of human presence. All that is left are traces, shadows, and ghosts. “The eerie also entails a disengagement from our current attachments”. But such disengagement, according to Fisher, “does not usually have the quality of shock that is typically a feature of the weird”. Instead, it is a “detachment from the urgencies of the everyday”. Many machinima reject the fast and furious pace of video games, preferring a more contemplative, slow, meditative approach. According to Fisher, the eerie “is constituted by a failure of absence and by a failure of presence. The sensation of the eerie occurs either when there is something present where there should be nothing, or is there is nothing present when there should be something.” Machinima often depicts things that look like people or environments, may even behave as such, but are not really people or environments. Disembodied voices, bodies without organs, selves that are others, artificial worlds, haunted spaces, a general sense of emptiness and displacement are quintessential traits of eerie machinima. Machinima, like Fisher’s concept of the eerie, “concerns the unknown”: what is this that I am contemplating? A lack of knowledge constitutes what he calls “the failure of absence”. A second mode of the eerie, “the failure of presence”, is “the feeling (...) that pertains to ruins or to other abandoned structures”. Eerie machinima often clings “to certain kinds of physical spaces and landscapes”. The representational spaces of many machinima, subsumed from post-apocalyptic or fantasy video games, fit the genre of ruin porn. And if the weird is associated with a sense of wrongness, “the eerie turns crucially on the problem of agency”, a central concern for scholars interested in digital games. Machinima fully and deliberately replaces agency with auteurship. Finally, eerie machinima is marked by “a sense of alterity” or Otherness. Unsurprisingly, machinima is often described in negative terms (“...not cinema”, “...not video game”, “... not video art” etc.). So, what is machinima?

Literally. After all, the Unreal Engine is one of machinimators’ preferred tools. A powerful game engine – a software-development environments used to create digital games – the Unreal Engine was developed by Epic Games. First showcased in the 1998 first-person shooter game Unreal and originally intended for first-person shooters, it is now used for a variety of other genres. Unsurprisingly, several machinima screened at the MMF were created by appropriating and repurposing video games developed with this tool. Some were created directly by using this tools, forgoing the need of subverting an existing game. Above all, machinima is unreal because it is “so strange as to appear imaginary; not seeming real”. The Oxford Dictionary definition of “unreal” perfectly fits a medium so strange, out-of-place, unnerving, unclassifiable, and incongruous as to make reality itself seem simultaneously weird and eerie. Because machinima is “an entity or object is so strange that it makes us feel that it should not exist, or at least it should not exist here”, we decided it deserved its own festival.

Weirdness exists in the interstices between media. Eeriness emanates from the ruins of dead ones. Unreality is the inevitable outcome of mediatization.

Machinima is weird, eerie, and unreal.

Matteo Bittanti

REFERENCES

Fisher, Mark. The Weird and the Eerie, Repeater Books, London, 2017.

The full essay will be available in the upcoming MMF catalog.