For the best viewing experience, we recommend watching the video in full screen mode.

The Death Trilogy

performance documentation, digital video and audio recorded in The Sims 4, 33’ 05”, 2024, Cyprus

Created by Adonis Archontides

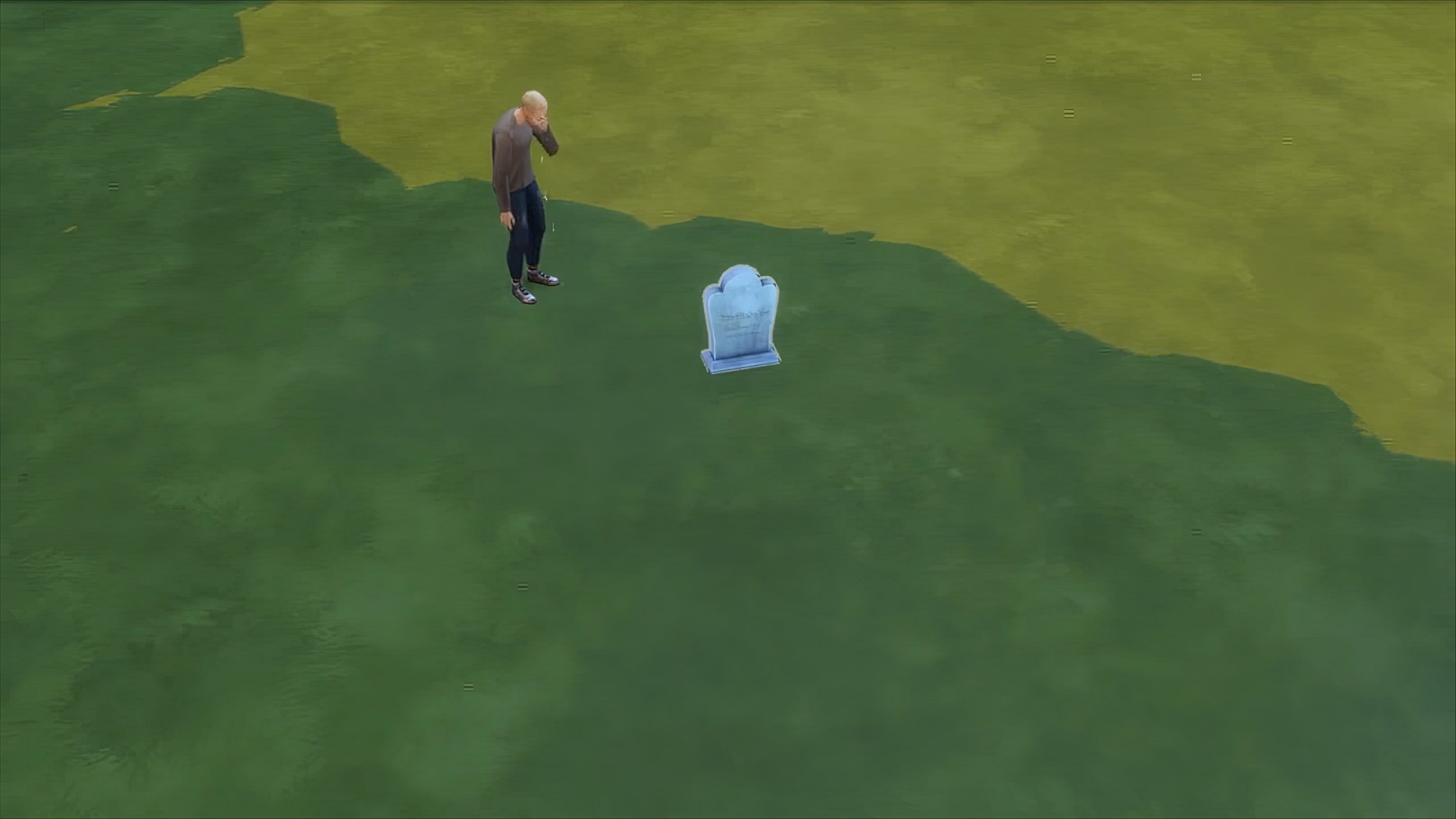

Za woka genava (I think you are hot), Ya gotta wob’ere! Ya gotta wob’ere! (Don’t give up! Keep trying!) and Za woka genava (I think you are hot) form a trilogy in which Archontides delves into the use of video games as a platform for documenting dual performances, those of himself and his avatar, Adonis (Sim), created within the popular simulation game, The Sims 4. This unique collaboration highlights a peculiar interdependence: although Archontides controls the outcomes of their joint endeavors, both entities contribute essential roles to their creative process. These performances unfold under the passive gaze of an audience, drawn into a somewhat sadistic voyeurism. Yet, crucially, Adonis (Sim) remains unaware of his reality as a digital construct, performing actions dictated by Archontides that, while impossible in the real world, are completely feasible within the game’s algorithmic constraints. The Death Trilogy pushes the boundaries of digital life and death, as evidenced in the final moments of each piece. Here, viewers witness Adonis’s resurrection, a thematic echo of the limitless possibilities afforded by simulated environments.

Adonis Archontides is a multidisciplinary artist who studied Illustration & Visual Media at the University of the Arts in London. His works are satirical and introspective; they often investigate the production of identity as a conscious or subconscious process, and the porosity between fiction, reality, and simulation. Part of his research focusing on his namesake Adonis, an ancient Greek nature deity, revolves around the effects of time on the interpretation of myths. An avid gamer, Archontides believes in the artistic potential of video games which often uses as raw material in his artistic practice. He has been collaborating with an avatar of himself created in the popular simulation game The Sims 4, juxtaposing Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey with an artist’s career trajectory through an episodic narrative. Archontides lives and works in Limassol, Cyprus.

Matteo Bittanti: You describe The Death Trilogy as a documentation of a performance within The Sims. How would you define these two keywords – i.e., documentation and performance – in relation to a video game? Does this medium alter their ‘message’ in any way? Or would you say that documenting a performance is nothing more or less than documenting a performance, regardless of where, when, and how such a performance takes place? What is the relationship between the resulting documentation, which in this case I would call machinima, and the ‘original’ performance? In short, could you elaborate on how you approach documenting these performances and what challenges and insights this method has brought to your artistic practice?

Adonis Archontides: In a video game context you would expect documentation to mean screenshots depicting the video game world, while performance would usually be some kind of eSports related thing, or even a speed-run, right?

Matteo Bittanti: Right! I am reminded of Henry Lowood’s influential essay High-Performance Play: The Making of Machinima, written approximately twenty years ago, in which he suggested that “game-based performance practices will influence work in artistic and narrative media”…

Adonis Archontides: That is a great reference! Even though our sort of performance is quite far (at least speed- and reflex-wise) from those original performances in Doom and Quake, they really did pave the way for everything we are doing today.

To try and answer your question, I feel like with The Death Trilogy, documentation and performance are layered as both myself and Adonis (Sim) are performing in different capacities... while at the same time both following the tradition of endurance art (a.k.a. durational performance). Endurance art usually involves some kind of hardship, such as pain or exhaustion, and the focus is to repeat an action over an extended period of time. I was reading a lot about that while researching existentialism in the years after graduating from university. There’s something about it that comes off as very honest for me.

While I’m not aware of any artists dying during their durational performances, the joke here is that Adonis (Sim) does in fact die at the end, but is able to come back as another version of himself to continue the work... In parallel, my endurance is focused on perfectly executing the run, which can take many many tries. In a sense, while filming, Adonis (Sim) is the artist while I’m more of an actor, repeating the same scene over and over again for the sake of the perfect take.

Matteo Bittanti: Right. To paraphrase Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, you are both an actor and an athlete, which brings us back to Lowood’s essay, with the added element of filmmaking and recording. To summarize: in video games, the player embodies several roles simultaneously. As a filmmaker, they direct the action, determining the narrative’s pace and the visual framing of each moment. In the role of an actor, players project themselves onto their avatars, delivering performances through choices and interactions that breathe life into the character. As athletes, they are always trying to improve his performance, smash existing “records” and so on. As spectators, players experience the consequences of their decisions and the unfolding narrative in real time, much like an audience witnessing a play. Beyond these roles, players may also adopt the perspectives of a photographer, capturing striking images, or an editor, shaping the presentation of the gameplay, or even a puppeteer, maneuvering characters and elements with precision. This multilayered engagement is all but manifest in your artistic practice, and is particularly evident in your extensive work with The Sims. This game not only influences but actively intertwines with your diverse creations, from sculptures and installations to photographs, videos, and even artist residencies. Could you describe your relationship to The Sims? What aspects of this playful simulation game do you find particularly compelling for artistic purposes, and how do these elements inspire you to create across such a variety of media? Additionally, could you elaborate on how The Sims shaped your conceptual and aesthetic approaches?

Adonis Archontides: I grew up with The Sims games. For some reason, we had a copy of SimCity 2000 on the Sega Saturn, and I would fumble around with it when I was a kid. When the first The Sims game came out, my parents got it for me on the PC and I spent countless hours on it – I’ve played every main edition since then. One of the most vivid memories I have with all of The Sims games is this inexplicable, almost primal instinct to recreate my family’s home.

Matteo Bittanti: I’m intrigued. Please explain.

Adonis Archontides: I’ve done it in every version, meticulously counting squares and estimating ratios based on the space a bed occupies. It’s interesting to consider this activity within the context of the Simulation Hypothesis — it sort of brings it back home where you're thinking “Oh wow, this could actually be me”.

At its core, however, the game to me is a storytelling vehicle, one that allows me to tell stories about my life and about my concerns without being the centre of attention or needing to hire actors and costly machines (even though my PC was quite an investment).

It’s also hilarious! I think humor is something I appreciate when I see it in art, and so I strive to throw hints of that in this series. There's always been a bit of self-deprecation… An artist playing at being an artist, playing at being a human. Where reality ends and real life begins.

I explored similar notions in my show Emotional Sculptures at a space called TestDrive in Nicosia... In The Sims 4, your Sim can get this bit of clay that takes different forms when the action is completed, depending on your Sim’s mood. I wanted to bring these sculptures out of the game and into the “real world” using Augmented Reality, and ended up engaging in another test of patience, as I decided that the way to go about this would be to start making them and not stop until I had all the variations. It was another durational performance experience, as well as an exercise in bringing layers of reality to the forefront.

Matteo Bittanti: Za woka genava (I think you are hot, Ya gotta wob’ere! Ya gotta wob’ere! (Do’n’t give up! Keep trying!), and Sulsul! Plerg Majah Bliff? (Hello! Can I do something else please?) make a clever use of many idiosyncrasies from The Sims, especially the use of Simlish. Could you describe the origins and development processes of these three pieces that seem to focus on a different element: fire, water and air (as the runner-in-place seems constantly out of breath?). Additionally, I’m particularly interested in the reception of these works as on-site installations. I’m specifically thinking of the show New Year, New You (2019) curated by Chole Stavrou. Could you share some insights into how visitors interacted with and reacted to these works during the exhibitions?

Adonis Archontides: Using Simlish for the title of the work really came at the last minute before the first time I showed Sulsul, and felt a little bit like an aha! moment that brought the whole work together. There’s a little dictionary of phrases online that I would refer to when naming these works. I hope it’s true, but I feel like everyone who knows a bit about Sims knows that “Sulsul” means “Hello”!

Matteo Bittanti: Yep! I can recall countless videos on YouTube of people having full conversations in Simlish... So, has the virtual always been at the center of your artistic preoccupations?

Adonis Archontides: My work has always been a form of self-psychoanalysis, or therapy if you will, but before embracing video games as a medium, my work was much more physically present. I had been exploring sculpture and installation through research into my namesake, the Greek vegetation deity Adonis. In mythology Adonis is life-death-rebirth deity originally worshipped in relation to nature and the seasons. Over the centuries, and as mythological stories became more complex and enriched by the people telling them, what remained of Adonis was that he was the beautiful young lover of Aphrodite. Emphasis on the “young and beautiful”, a standard meant to be upheld by his namesakes. So you see how that can be a problem…

I started working with The Sims through Adonis and The Labour of Artistic Production, which was a residency based in The Sims 4 that I created for myself. I had been struggling with balancing real-life work with finding time to work on my art (for example, I was never able to go do residencies, as that would conflict with my day job). So I decided what better way to deal with it than to make my own space, a digital one that I could attend to every evening after work, in the comfort of my room. You see the pattern with trying to solve life problems with art?

Matteo Bittanti: Mos def. I’m eager to know what happened next…

Adonis Archontides: Adonis (Sim) and I made a bunch of work for that residency, and coming out of it I was feeling like the next step had to be active in some kind of way. I was invited to a duo show here in Cyprus, and I knew I wanted to somehow bring together the mythological Adonis with the digital one. I had been already planning on creating a new installation called Bath which was a makeshift pool inspired by and named after the Adonis Baths here in Cyprus, allegedly the birthplace of Adonis. There’s a (quite vulgar) poem there supposedly invigorating the waters to grant men renewed virility, which was transcribed onto my artwork.

While working on this project, the thoughts in my head were constantly revolving around stories, the stories we tell to others, the stories we tell to ourselves, the stories we tell to others about ourselves. How these exist in the different levels of reality I mentioned earlier, and where virtual worlds fit into all of this equation.

Matteo Bittanti: For the record, how many levels are we talking about?

Adonis Archontides: There was Adonis the real (me), whatever that means. There was Adonis the god, the mythologically fictional. There was Adonis the ideal, the contemporarily fictional. There was Adonis (me) the artist, a wholly different being from the original, and now there was Adonis (Sim) the Virtual, the digital avatar.

So in my headcanon, Adonis (Sim) got imbued with Adonis (god)’s powers of immortality, by extension of his digital ever-replicating nature.

Growing up I thought there was something wrong with me for the kick I was getting out of finding creative ways to kill my Sims. Maybe there’s still something wrong with me, but I’ve since discovered that a lot of people did the same thing.

Matteo Bittanti: Yes! We’ve all been through the sadistic stage. I remember a talk by Will Wright at GDC on this very topic. Early Zeroes…

Adonis Archontides: That’s hilarious that it got so big that even Will Wright would comment on it! I really need to watch this GDC talk! So yeah, I remembered the whole pool killing thing and went to replicate it in The Sims 4. Apparently now you need to build walls around the pool because your Sims can get out from anywhere – ah, the advancements in technology. I decided to record it, and eventually came to think that this was the kind of funny fucked up artwork an immortal god would create.

Matteo Bittanti: …And how did it make you feel? [using a somber shrink voice]

Adonis Archontides: I suppose, it was some kind of cathartic process? I’m sure a psychologist would have a field day analysing what making an avatar of yourself and killing it over and over again to make your little movie could mean.

Matteo Bittanti: …That’s remarkable!

Adonis Archontides: By the way, I had never really thought of this association with the elements, it’s a pretty interesting one! Maybe this means I should complete what should be a tetralogy with another performance based on earth. Then Adonis (Sim) will finally be The Avatar.

As for New Year, New You (shout out to David Raymond Conroy for his project Retail Space which allowed us to rent the space out for the day for the exhibition), I must confess that I don’t really know how viewers reacted to that exhibition. Unfortunately I couldn’t be there :( The photos came out nice at least!

For me, it was really important for all three of the works to come together on a large scale. I always imagined them as video installations, just running in the background. The repetition is sometimes calming, hypnotic, almost meditative until eventually DEATH HAPPENS. So standing in the middle of these three large projections must have been quite immersive.

Matteo Bittanti: The concept of infinite lives in video games profoundly affects how narrative can unfold in digital environments. How does this concept influence the narratives you create for Adonis (Sim), and what do you aim to convey through these recurring loops of death and resurrection? How do you use this motif to explore broader philosophical or cultural questions? What significance does this cycle hold in the context of a digitally simulated environment?

Adonis Archontides: I mentioned earlier about how most of my work is psychoanalytical in nature, as well as this identity crisis situation, being torn between different performed variations of yourself which are then in constant battle with the idealised versions.

I can’t say I have much interest in actual physical death as much as I have in the (many) metaphorical deaths we experience over our lifetime, with each little death saying goodbye to a previous version of yourself and welcoming the next one in. It’s a constant battle towards evolution, a concept we’re all too familiar with as gamers.

Jesper Juul talks a lot about it in The Art of Failure, how failure in video games provides a unique experience that allows players to experiment with inadequacy and escape it through improvement.

As a person with (self-diagnosed) ADHD, quite often struggling with focusing on research and work, video games are the one realm where I can actually focus – which is also a reason why I use them in my artistic practice as well.

Having said that, there’s also the opposite end of the spectrum, where trying too hard, trying to keep up with the hectic rhythm of contemporary life, leads to overexertion. It’s a very fine line of balancing the two ends of the spectrum – self-development and self-exploitation.

Matteo Bittanti: In your work, you constantly manipulate and orchestrate scenarios within The Sims to reflect both on societal issues, personal narratives, and medium-specific affordances. Given the control you have in shaping these virtual lives and environments, could you discuss how this power dynamic between creator and creation might mirror or critique societal structures of control and governance? How does this interplay between control and autonomy within your work provoke thought about our own reality and personal agency? And how do you define agency? Can you discuss the limitations and freedoms these algorithms provide in the context of creating meaningful art?

Adonis Archontides: That’s a really complex and difficult subject, especially in this day and age, when our lack of control is becoming more and more apparent. I come from a country with a highly corrupt political regime (as evidenced by the Cyprus Papers and Golden Passport Scandal). Money is the main drive – if something doesn’t serve a financial purpose then the government isn’t really considering it. There has also always been a feeling that the people just let things happen to them, they just accept the status quo as it is.

There’s a great scene from the first episode of season one of Westworld. Spoiler alert. An examiner, Bernard is doing a control check on Dolores, and reveals to her that her whole life is just one big simulation – every day of her life is pre-scripted, everyone she has ever known was created in order to gratify the desires of the people who pay to visit Westworld. And there’s nothing she can do about it. He asks her if that changes the way she thinks about these people. She responds, “Of course not. Every new person I meet reminds me of how lucky I am to be alive. And how beautiful this world can be.” It’s a beautiful analogy for appreciating the world, no matter its flaws.

Matteo Bittanti: This feels like the exact opposite of that scene The Matrix where Agent Smith reminds Cipher that reality is a simulation, and the latter responds, looking at the virtual piece of steak he’s greedily eating, “Ignorance is bliss”…

Adonis Archontides: Whether it’s ignorance or complacency, I’m looking forward to the day that both my Sim and the world start saying “No”, so it’s my hope that watching the work will get you really thinking about your own levels of agency.

Matteo Bittanti: I feel your work is engaged in a dialogue with Angela Washko’s seminal Free Will Mode, as they both address similar themes. Speaking of agency, in Adonis and the Lockdown Tactics, which we screened in 2021 in the context of the Milan Machinima Festival, you employ a sci-fi trope of recursive, looping narratives to illustrate the monotony of daily life during the Covid-19 pandemic. Considering your previous works that explore the cyclic nature of life and resurrection in digital environments, could you discuss how this theme has evolved in your artistic practice through the lens of both machinima and the lived human experience? Did life during the lockdown become indistinguishable from a nightmarish version of The Sims for you? What do you remember about a time that seems both recent and ancient? How did video games help you cope or even prepare for the lockdowns?

Adonis Archontides: Lockdown Tactics was really a very natural progression to the Sims Saga (I like to think of the entire series as a Saga, one to be continued in due time and eventually completed). This virtual character who we’ve established can never fully die, and has spent a good chunk of his life dying and coming back to life for a performance piece, was now also stuck indoors, with little variation to differentiate one day from the next. I watched Groundhog Day for the first time that year, and I knew I just had to implement it somehow.

Fun fact: Ideally, that work (made up of four scenes in three variations) would actually have a lot more than three variations for the four scenes, and the machine they’re played on would randomly pick a variation to play, and keep going perpetually on loop.

As for COVID... to be honest, I was really enjoying myself. It was good to slow down, not have so many distractions. Almost no pressure to be social (something I go through phases of really dreading) – for my mind, at least. My days had structure, and that gave me a decent amount of pleasure. Seeing how things turned out post-Covid, one almost wishes to just return to that.

There’s worse things than being stuck indoors.

Matteo Bittanti: I couldn’t agree more. I truly miss the lockdowns. In fact, I think we should mandate them annually, for an entire month. It would be the antithesis of The Purge. We could call it The Quiet. Imagine it: less pollution, less chaos, less violence. And, as a form of social service, members of the elites would personally deliver food to the masses, right to their doorsteps. I mean, as Peter Turchin argues, we are facing an elite over-overproductionand these poor souls don’t know what to do with their expensive skills and abundance of time. I think we should be put to a good use, don’t you think so?

Adonis Archontides: Haha, we really should campaign for that. I love The Quiet. (Even though I kinda love The Purge, too). At the beginning of the first lockdown, there was an instinct to make work, to use up all of The Quiet time to be productive. I made some drawings, some paintings.

Matteo Bittanti: First and foremost, be productive! Playbor uber alley! Let’s keep the charade going. “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of…” etc.

Adonis Archontides: We’ve spoken many times about this, but my videogame photography series Postcards from Quarantine was also born during that period – a series of images I took in the videogames I played during the first lockdown. Being able to “travel” through those games really helped to keep my mental health in check.

That being said, while overlapping playing games with artistic production (you called this “playbor”, a term I loved (1)) is a much more fulfilling process than the physical work I had been doing previously, I can’t help but feel that it was just another part of my life, one that had been giving me pleasure, that I was now exploiting for the sake of work.

The Capitalist machine grinds on, and all the while Adonis (Sim) keeps on running.

Note

Credit where credit is due: the term playbour was coined in 2005 by Julian Kücklich in his essay for Fibreculture journal.

The Death Trilogy

performance documentation, digital video and audio recorded in The Sims 4, 33’ 05”, 2024, Cyprus

Comprising:

Sulsul! Plerg Majah Bliff? (Hello! Can I do something else please?)

Za woka genava (I think you are hot)

Ya gotta wob’ere! Ya gotta wob’ere! (Don’t give up! Keep trying!)

Technical details:

Performance documentation, digital video and audio recorded in The Sims 4, 31’38’’, 2018.

Performance documentation, digital video and audio recorded in The Sims 4, 25’04’’, 2019.

Performance documentation, digital video and audio recorded in The Sims 4, 10’48’’, 2019.

Made with The Sims 4 (Electronic Arts, 2014)