FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Over 500 Attendees at Italy’s First Conference on In-Game Photography

Milan, Italy – IULM University hosted the pioneering Fotoludica conference on March 14 and 15, 2024, marking a significant milestone in the recognition of in-game photography as an emerging art form. Curated by Matteo Bittanti and Marco De Mutiis, the event attracted over 500 participants, highlighting its success and the growing interest in this cutting-edge field.

Fotoludica, brought together a diverse group of attendees, not limited to IULM students. The conference saw participation from students across various universities and art schools, including a notable class from the Milan Academy of Art of Brera, led by esteemed curator Domenico Quaranta.

The event unfolded in the Sala dei 146 at IULM 6, Università IULM, offering two days filled with insightful talks, presentations, and discussions. It served as a vibrant platform for creators, researchers, and theorists to explore the intersections of video games, photography, copyright law, activism, and visual culture.

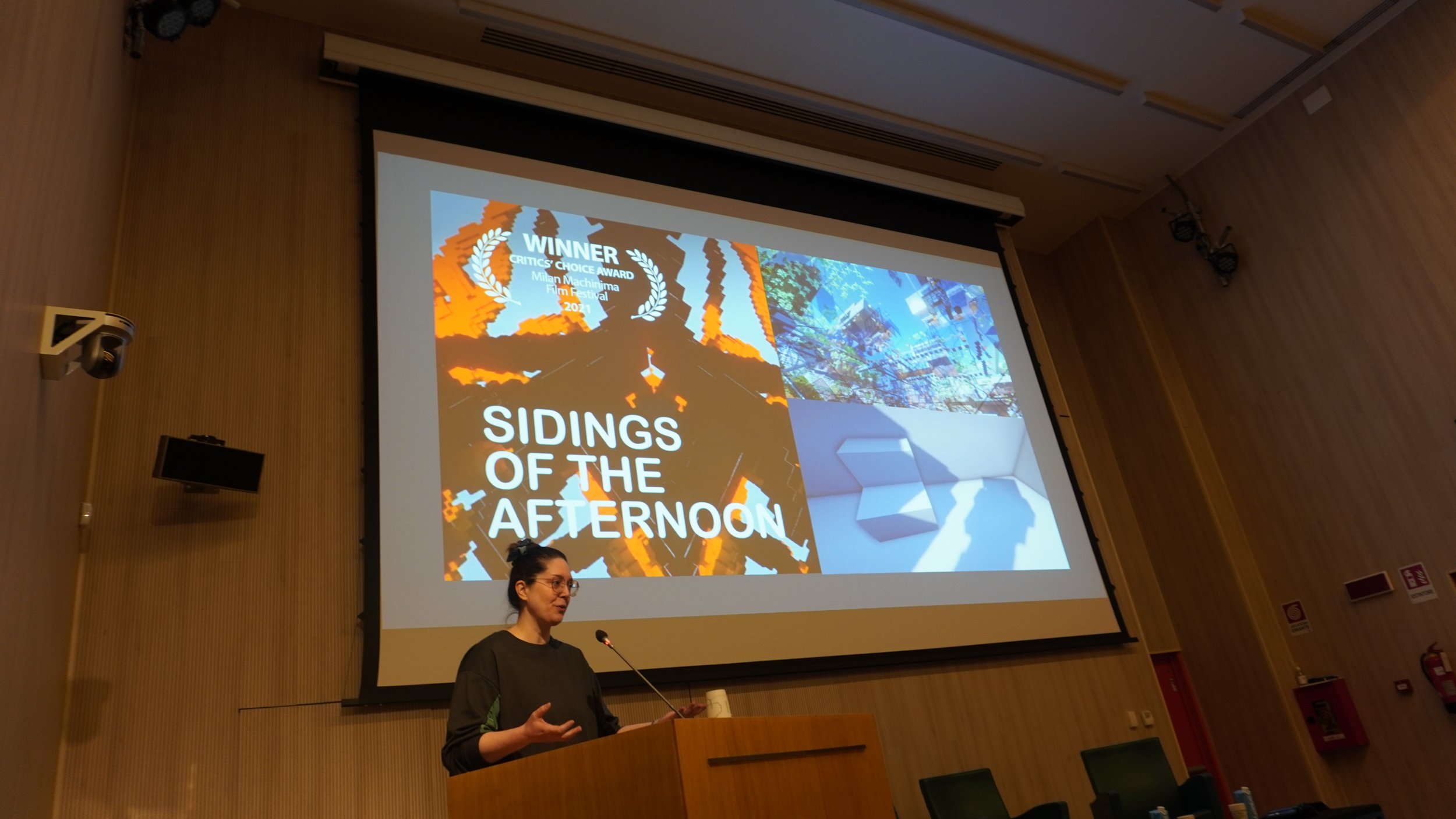

Fotoludica tackled various facets of in-game photography, from the artistry of photo modes and screenshot hacks to the legalities concerning player-created images. The conference featured analyses of works by renowned artists such as Boris Camaca, Leonardo Magrelli, Simone Santilli, Alan Butler, Pascal Greco, Joseph DeLappe and Adonis Archontides, showcasing the depth and creativity possible within virtual gaming worlds.

Key topics included the use of photography for architectural visualization in games like Minecraft, documenting in-game performance art, and contemporary war photography. Discussions delved into the ways gaming environments, when viewed through a photographic lens, can expose themes of violence, labor exploitation, and colonial ideologies.

The lineup of speakers spanned diverse fields, including art history, visual culture, game development, and internet law, with keynotes by Marco De Mutiis on “Playable Imaging” and a special conversation between artist Joseph DeLappe and scholar Laura Leuzzi. Panel discussions led by Bittanti and De Mutiis critically examined the boundaries of creativity, authorship, and ethics in photographic practices using game engines.

Fotoludica has not only established in-game photography as a significant art form but also underscored IULM University's leading role in the scholarly exploration of photography within game studies. The conference’s success in fostering multidisciplinary dialogue sets a new benchmark for artistic interrogation of games, bridging the worlds of photography and machinima.

Fotoludica was the first of a series of events organized by IULM University on the topic of in-game photography as part of an ongoing research. Additional initiatives will take place in May 2024. For more information on the Fotoludica conference and its contributions to the field, please contact Matteo Bittanti at matteo.bittanti@iulm.it

Contact Information:

Università IULM

Via Carlo Bo, 2

20143 Milano

Event Information: Fotoludica

Date: March 14-15, 2024

Time: 10 AM - 1 PM

Location: Sala dei 146, IULM 6, Università IULM